What Happens When You Make It Free? How the Price of Zero Affects Users

In the real world, very few of the many systems that influence commerce are linear, given enough time; and once a zero comes into the mix (like when you make something free), customer behavior changes quite a bit.

When you make a product free, you introduce not just another number but a concept that often changes an individual’s behavior, for better or worse. Here we’re going to discuss the systems that come into play when “zeroes” and free stuff are offered to consumers.

People exhibit irrational behavior when a zero is involved, though it’s often predictable

Dan Ariely, who has extensively studied seemingly irrational human behaviors, finds they’re often quite predictable, a topic he discusses at length in his book, Predictably Irrational.

While several external factors influence us, most of us go through the same cognitive processes when processing information. | Source: OpenStax

For example, Ariely demonstrated that we tend to think of more expensive, recognizable names as being better through his aspirin experiment, where people showcased a placebo effect. So long as a person believes they are taking a Bayer aspirin, the aspirin will perform as such, whether the aspirin is indeed Bayer or a generic store brand.

We also tend to use other contextual data in an environment, usually unwittingly, during decision-making processes. Because human learning is driven by association and comparison, this and other connected behaviors are frequently observed when studying commerce, whether in the real world or through digital products.

Some free is better than other free

Two free items could literally be the same thing, but with a little guided perspective, one can stand out as a better option to a consumer.

In another example from Nir Eyal in his book Hooked, he uses a cookie jar example in which two cookie containers are placed side-by-side with the same cookies, with one being nearly full and the other almost empty.

When people were asked to choose a cookie from one of the jars, most went for the jar with fewer cookies.

If you’re on a diet and this happens to you, the rules say you can cheat that day. | Source: Filipp Romanovski on Unsplash

While other factors affect our decision-making, specific patterns emerge when studying the general population. For the most part, systems will follow a trend until hitting a particular point, especially when a zero comes into play or something becomes free.

Predicting behavior around zero

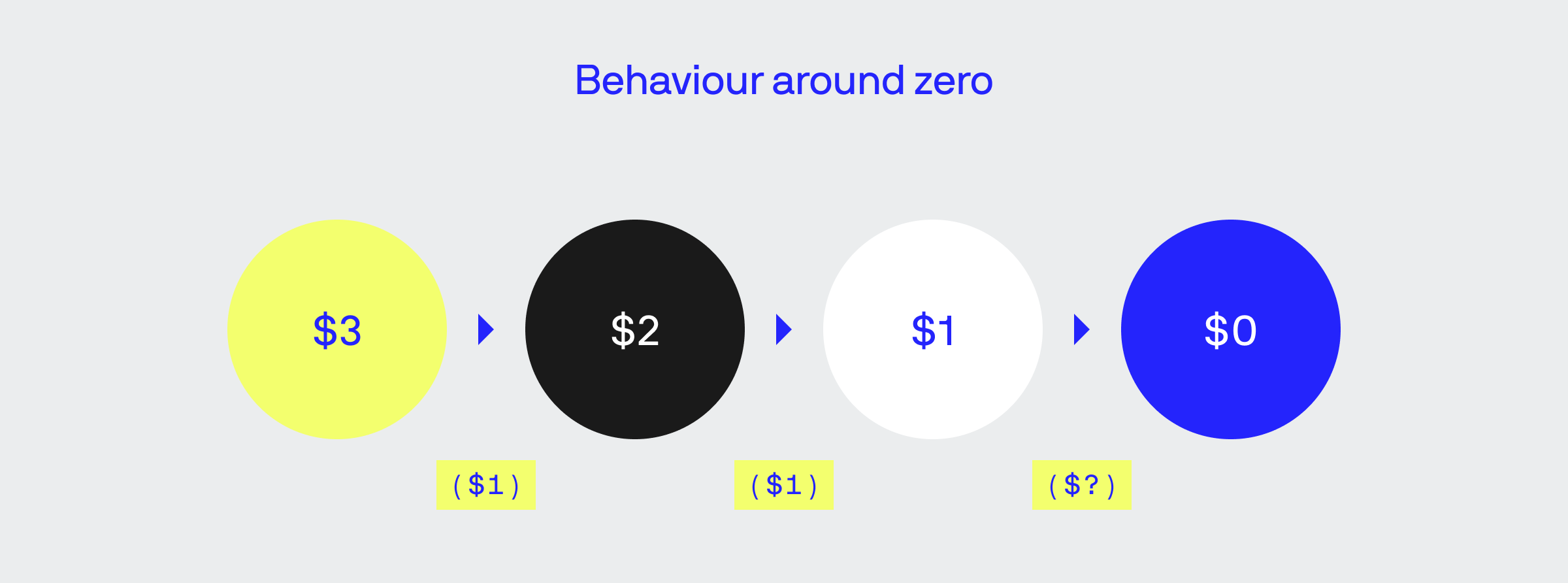

Zeroes are weird – they throw us off like a division error in Excel. But when focusing on price, specifically when an item or service is free, you tend to see significant (i.e., exponential) change.

When you start changing the price of something, let’s say a $5 item, you should see a fairly linear increase in interest (assuming appeal and supply remain constant) as you successively subtract $1 from the price.

But once you get to zero, an appealing product might be perceived as far more valuable than it actually is.

As people, we have a few fascinating notions about pricing that marketers leverage to create appeal from nothing.

In one notable example from Chapter 3 of Ariely’s book, Predictably Irrational, he first discussed how, during an experiment, people seemed to strongly prefer a free Hershey’s Kiss chocolate over an attractively-priced piece of truffle chocolate. The disparity in people who chose one of the other was relatively mild and followed a modest trend as the Kiss’s price continued to fall, that is, until it reached zero and popularity skyrocketed.

Of the many truths in this world, none are more valid than the fact that not all socks are created equal. | Source: Lum3n on Pexels

In his next example, he reflects on a hypothetical situation where someone might set out to buy a nice set of socks but end up with an inferior product because the packaging allured them with a couple of free pairs. This is then tied into another experiment where people, when given the option, would select free chocolate, despite the paid option offering six times the return compared to what the free product offered.

When something “free” is provided along with a paid item, the former almost always attracts people, provided the service is desirable in the first place.

Free isn’t always valuable

We’ve built and supported many products that use a freemium model when it often proves beneficial for that particular project.

The determination to do so is driven by data – while free does usually get people’s attention, something that’s free out the gate needs to have staying power that keeps users around.

This app has been around for a while because it does several things right, but it’s not for everyone. | Source: Google Play

In Hooked, Eyal discusses his attempts to lose weight and discusses how he used MyFitnessPal to help him with accountability in his diet.

He acknowledges that it’s a great app for its intended use, but the problem was that he wasn’t a calorie counter in the first place. He speculates how it would be ideal if he were coming from a slower, less sophisticated method to count but found the experience, as someone new to the process, tedious and frustrating at times.

Most digital products must demonstrate value to prospective users and offer the ability to “invest” in the product. In this context, “invest” refers to a user’s ability to take actions like performing customizations well as the product’s ability to retain breadcrumbs of the user’s activities. This sets the stage for the user to establish a habit, which is the goal of many products.

Not all appealing products can be directly monetized

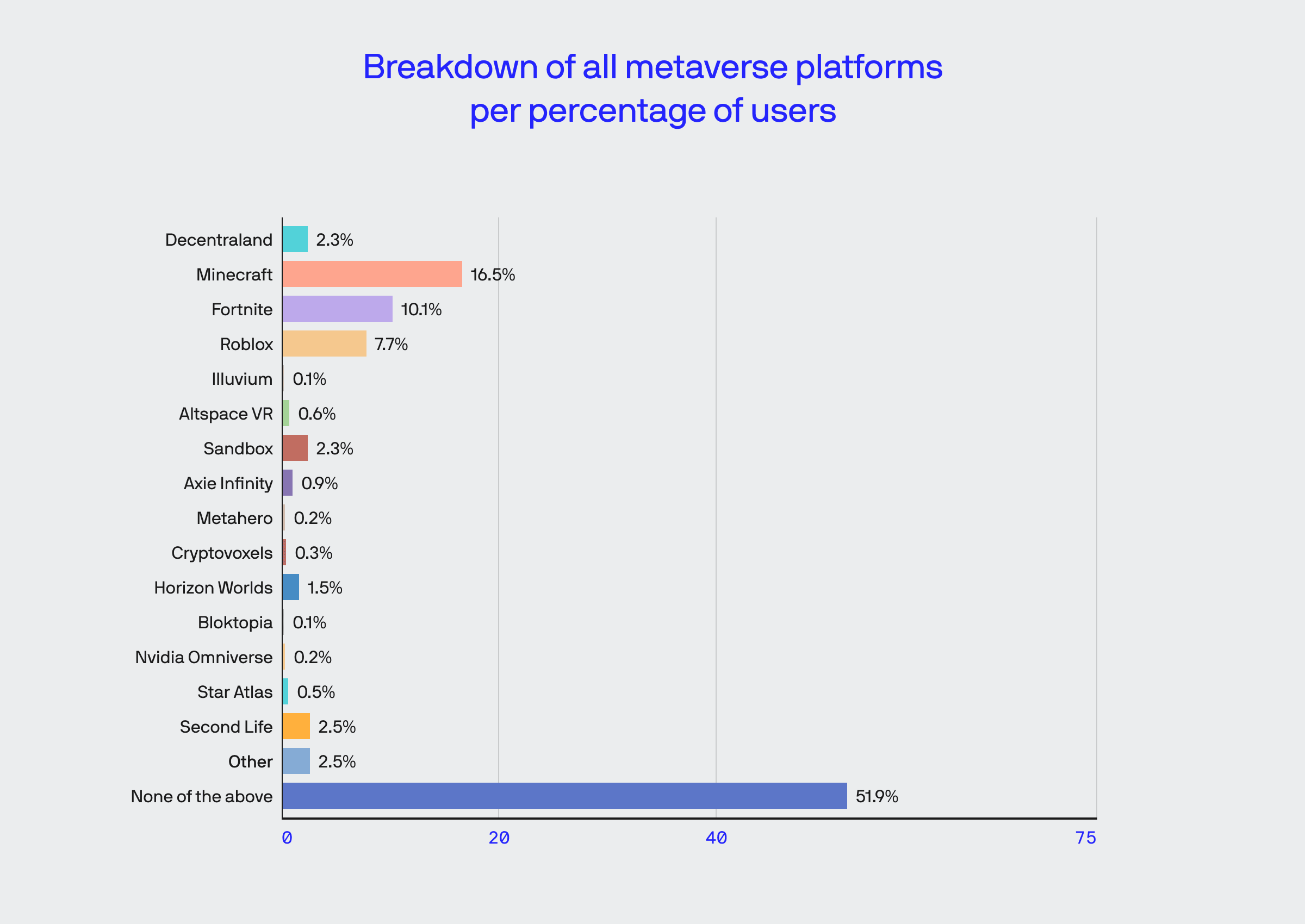

Our recent metaverse study showcases an excellent case in point for this fact.

Learn more by visiting the write-up from our metaverse study.

The metaverse has been toted as this up-and-coming trend that, despite being around for almost two decades, is supposed to transform how we do business.

The problem is that despite the concept’s ability to attract a modest number of users, most people aren’t that interested in using the metaverse for monetary gain: they use it for fun.

Only 3% report using their favorite metaverses for financial gain, though many can be extremely lucrative.

In our last example, Eyal discusses how the Q&A site Quora rose to fame not because it pays users financially but because answering questions often provides “rewards from the tribe,” meaning community validation.

In this sense, it’s much the same as any other social platform.

Quora beat out an emerging platform known as Mahalo, which was becoming popular by providing similar functions and paying users who provided valid answers. However, its popularity waned, simply because “people will forgo money (to a point) in order to disclose about the self.”

This can be back to observations discussed by Ariely about mixing social and market norms. For more information about this interesting mechanic of society, feel free to watch the quick video below before you go.